December 5, 2011

November 30, 2011

The Long and Tangled Madrigal of Time

History's Madrigal

Robert Morgan

When fiddle makers and dulcimer

makers look for best material they

prefer old woods, not just seasoned

but antique, aged, like timbers out

of condemned buildings and poles of

attics and broken furniture

from attics. When asked, they will say

the older wood has sweeter, more

mellow sounds, makes truer and deeper

music, as if the walnut or

cherry, cedar or maple, as

it aged, stored up the knowledge of

passing seasons, the cold and thaw,

whine of storm, bird call and love

moan, news of wars and mourning, in

its fibers, in the sparkling grain,

to be summoned and released by

the craftsman’s hands and by careful

fingers on the strings’ vibration

decades and generations after

that, the memory and wisdom of

wood delighting air as century

speaks to century and history

dissolves history across the long

and tangled madrigal of time.

poem via robert-morgan.com

Ritchie Family Christmas Reunion 1955

Before you hang that Christmas tree, look to the Ritchie's for some ideas. The episode was filmed for the Dave Garroway Show in 1955. According to Jean, the filming was "hurried because much of our time was taken by a last-minute decision by NBC to show President Nixon lighting the D.C. Christmas tree." Enjoy.

Bio of Jean Ritchie:

It is impossible to place any one label on Jean Ritchie. She is a traditional musician by virtue of her life and works, but she is also a commercial performer, author, recording artist, composer, and folk music collector.

Ritchie was born in 1922 in Viper, Kentucky, into a family that considered music extremely important. In addition to singing as a means of entertainment, they had songs to accompany nearly all of their activities, from sweeping to churning to working in the fields. When they got together in the evening to sing as a family, they chose from a repertoire of more than 300 songs. Among them were hymns, traditional love songs and ballads, and popular songs by composers like Stephen Foster. For the most part, these songs were learned orally and sung without accompaniment.

While much of the music that was to become central to Ritchie’s later performance repertoire originated at home, other influences on her musical development cannot be overlooked. Besides the songs of family and friends, she was exposed to the music of the Old Regular Baptist church meetings the family attended regularly and to popular culture, particularly radio and recording. It is interesting to note that the one thing absent from Ritchie’s musical background is formal training.

After graduating from high school in Viper, Ritchie attended Cumberland Junior College in Williamsburg, Ky. From there she went to the University of Kentucky, where she graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1946. With a bachelor’s degree in social work in hand, she moved to New York City to work at the Henry Street Settlement. There she drew on her knowledge of family songs to entertain the children in her charge.

Gradually, Ritchie’s reputation as a folk singer grew, and she was asked to perform more formally. (Many of these concert experiences are discussed in the video.) For folk music fans of the 1940s, Ritchie represented the ideal traditional performer: She grew up in the mountains of Kentucky, sang songs that she learned from her family, and played a little-known instrument called a dulcimer.

Ritchie has maintained an active performance schedule ever since. She has played and sung on radio and television, in concerts, and at folk festivals and hootenannies in the U.S. and abroad. As you will see in the program, her friends and acquaintances include many of the most recognizable people in the contemporary folk and country music scenes. When Ritchie’s album None But One won the Rolling Stone Critics’ Award in 1977, her acceptance into the popular mainstream was secured.

bio and photos via ket.org

November 29, 2011

'Moonshiners' on Discovery

It was only a matter of time... Check out the trailer, and then rinse yourself off with some scholarship.

- Hillbilly Culture: The Appalachian Mountain Folk in History and Popular Culture

- Back Talk from Appalachia: Confronting Stereotypes

- Appalachian Culture and Economic Development

- Appalachian Culture and Reality TV: The Ethical Dilemma of Stereotyping Others

- West Virginia's Lost Youth: Appalachian Stereotypes and Residential Preferences

A Thousand Little Cuts

Chad Stevens is working on a film and needs help. They've set up a print auction fundraiser, selling some really fine prints shot by some really fine artists. Proceeds will be used to complete the film A Thousand Little Cuts, a six-year documentary project exploring the grassroots movement to stop the highly-destructive mining process, mountaintop removal. The main character, Lorelei Scarbro, a tenacious grandmother of two, fights for green jobs and renewable energy projects in her community; but with a brother working on a mountaintop removal mine and a son-in-law working for Massey Energy, the risks are grave. In a place where blood and coal tie families together, Lorelei’s campaign to save a mountain could destroy the very thing she’s fighting for: her family.

Find more here: http://athousandlittlecuts.com

From Chad:

The road to Cumberland, Kentucky is all switchbacks, the asphalt snaking up and down Pine Mountain. My students and I had driven this road many times during the weeks we traveled to the small coal-mining town to make photographs, but this time we stopped near the peak. And we watched.

In the valley below us, great machines were moving earth and stone – building more access roads for the coal trucks. To the west we saw a barren bulge in the landscape – once a great mountain, now it was shaved flattop by dynamite. As we began to roll on toward our destination, the sun rose, lighting the ridgeline and the morning fog boiling in the valleys.

I realize now, six years later, that was the moment. Anti-mountaintop removal activists have a saying: “We all have THE moment – the moment when we knew we had to do everything in our power to stop the most destructive assault on Appalachia in history.” They started making protest signs and organizing rallies. Others brought chains and locked themselves to bulldozers. Some marched to Washington to lobby legislators. I started taking pictures.

I grew up in a small town in Kentucky on the far western edge of Appalachia. I stumbled into a photojournalism class in college and discovered that I was in the top school for documentary photography in the country and that I loved telling stories with the camera. I interned at newspapers, then at National Geographic Magazine. I lived in Uganda creating my first multimedia projects on rural education programs and AIDS orphanages. I used the camera to fight what I found wrong in the world, letting the characters in the projects voice their own stories, empowering them and informing others.

Now six years after my “moment,” I have transitioned from a documentary photographer to a documentary filmmaker. As I made those first images and began exploring the hills and hollows of West Virginia and eastern Kentucky, I realized the stories here were complex, perhaps even beyond what can be captured in a 35 mm frame. I began recording audio. HD video soon followed, then the new HDSLR system. Simultaneously, I began editing short documentary films at MediaStorm, a social advocacy documentary production studio in New York in 2007. I produced and edited projects that were nominated for two News and Documentary Emmys, won one Webby for Documentary, won a Silver Baton in the Alfred I. DuPont Journalism Awards, and the Online News Association Award for Video Journalism.

I moved back to southern Appalachia so I would be able shoot as the story continued to unfold, and now, 250 hours of footage later, I’m nearing the summit: the completion of my first documentary film, A Thousand Little Cuts. I’m in the final stages of production and have completed several trailers, extended teasers and am now assembling scenes. It is absolutely the most challenging project I have ever attempted. It’s a dynamic process layered with excitement and fear, hope and loss, connection and empowerment. But it was never a choice to be made. I have to do it. I had to take the first steps on this journey. It’s who I am.

November 17, 2011

Food & Faith: The Latest From CONSP!RE Magazine

Sandwiched between stories of urban gardening, musings on food and faith, and reimaginings of a more healthy sustainable food system, sits a portion of my conversation with Wendell Berry in the Fall 2011 issue of CONSP!RE (a project of The Simple Way). From their website:

"CONSP!RE is a magazine committed to building relationships and nurturing those trying to follow the way of Jesus. It is supported by a network of communities, groups, and individuals. Each issue explores the questions of faith that arise from living for justice and as part of the body. CONSP!RE means breathing together. We believe the reign of God is about relationship and living with imagination. CONSP!RE also means plotting together—and we are plotting goodness. We yearn to do small things with great love, interrupting injustice with grace, and transforming ugliness to beauty."The Fall 2011 issue of CONSP!RE focuses on food, land, fellowship. Its premise is straightforward: the food system is broken, and each of us is capable of taking small, revolutionary acts to heal it. Just to prove it, there are going to be dinners all over the country during the month of November. Check out a CONSP!RE Gather Round dinner near you!

Each time we eat, we have the chance to build community, to eat food produced in a way that sustains our land and those who work upon it. Every day, we have the chance to express the essential holiness of the meal. You will find the voices of farmers, foodies, and everyone in between. This issue is the doorway into a host of resources to reboot your relationship to food. Be inspired. Go plant something!

November 16, 2011

Hollywood Heads to Floyd County, Virginia

Ax Men, one of those rough-and-tumble Ice Road Truckers kind of shows from the History Channel, spent the last couple of weeks filming with Jason Rutledge of the Healing Harvest Forest Foundation. Way to go HHFF!

Here is an excerpt from my 2009 interview with Jason. Here, he reflects on his early days on the farm and the influence of his grandfather on his life and work:

"After serving as a mentor to many younger horsemen over the years it’s interesting to reflect on those who influenced me in the past. Born to a teenager in 1950, I was raised primarily by my grandparents. My male role model was my grandfather, Willie Farrar, who I called Papa. Papa was born in 1905. His father was a Sergeant in the Confederate Army and fought in the civil war. They lived on a farm at a time when animal power was the only method available to average people in rural America. Papa was illiterate and couldn't read or write much more than his name, though he could count pretty well. My grandmother said he had no choice but to work on the farm to help the family survive the early parts of the twentieth century.

My family was poor, but there was always plenty to do. My earliest memories include the life of being a sharecropper in Southside, Virginia, a place that came to be called Tobacco Row. We would move from farm to farm making crops that we would sell at markets. Our work was always done with black sharecroppers who lived in tenant houses on the farms where we worked. We all worked together and shared the proceeds equally.

I remember waking up in a tobacco slide on the way to the pack house being pulled by a gray mule. The mule operated on voice commands and knew exactly what to do. I never remember Papa being loud with his animals. He was always quiet and deliberate with them. I remember he always had favorites because those were the ones he would allow to baby-sit me. I often rode them while he worked, holding onto the hame balls, part of the harness tack on a horse team.

I remember the smell of sweat, human and animal, and the smells of tobacco, sorghum, sawdust, and manure. After the crops had been sold, the molasses made, and the hogs killed, we went to the woods for the winter and worked there until it was time to put in the plant beds for the coming season.

At this time, there was of great abandonment of farms throughout the country. People were moving to towns and cities to find work in factories and industry instead of maintaining a life on the farm. My grandmother always had a job in town as well as working at house and on the farm. Papa did the farming and looked after me. Since he made his living by working with animals, I was exposed to the skills of farming and logging with horses and mules from an early age. Papa was my mentor without me even knowing it.

As I grew into a teenager, my grandmother, as she describes it, “Broke Papa of his farming habit.” He would work a public job as a tractor dealer or head into town to see what other work was available. But he never quit messing with animals. He had a relationship with the man that ran the killer barn that slaughtered horses for export. It was called Cavalier Export. This fellow would call and say he had a nice pair of horses and Papa and I would go pick them up and bring them home. The killer man didn't like killing good serviceable animals, so it was a win-win for him and Papa.

Papa and my grandmother finally bought a little piece of land that sat on the side of a major highway between Lynchburg and Richmond. He had a big garden that was visible a long distance from both directions. He would bring the workhorses home from the killer barn and work them in that garden spot until they were content to stand. He had me make a sign for the roadside that read: Garden Horses For Sale. We would drive the horses around and around the patch of tilled ground until they would learn to stand quietly. Papa would sit under a white oak and sip on a PBR that he kept hidden in a cinder block hole under a board where I sat. He always pretended to hide it from grandma, but she knew it was there.

During these years I met other horsemen and farmers who all addressed my grandfather with great respect. I remember his being called to pull out trucks that were stuck in the woods and in ditches. People throughout the community called him to work their gardens. He’d always go if it was within driving distance with the animals—and he always included me in those activities. We enjoyed the work together.

After I went on to school and did some military service, I came back to the area and found land that I could afford. When Papa was on his deathbed he told me to go to the farm and get all the stuff I wanted to farm with. I still have some of his plows and hardware today. When logging with one horse I still use his singletree to bunch logs for the team or to train young horses in the woods. I feel very lucky to have had this cultural background and I try to offer the same experiences to every young person I can. The important thing about being a mentor is recognizing how important those early experiences are for beginners. Those are experiences that will last a lifetime."

November 10, 2011

Handcrafted Beauties From Larkspur Press

Larkspur Press in Monterey, Kentucky create some of the finest handcrafted books, special editions, and broadsides you'll ever see. Their work is technical and detailed, yet the vision is simple:

"What we try to do with our Craft and Art is to publish in a well designed, well made way. Our focus is on the writing. Artwork is used to complement the Poem or Story. We try to publish an edition that is affordable. Most of the writers we've published are living. Many of our books have been the Author's First Book, and the work of many of them is now well known. We've also had the privilege to work with many established writers.

In addition to publishing, we are helping keep alive the traditional Art of letterpress printing, which is shown in the special editions we issue, along with the more affordable regular editions.

It is fun work. Over the years there have been many Apprentices at the press, but the folks now responsible for the work are Leslie Shane, Carolyn Whitesel and Gray Zeitz.

All our work is handset in metal type and printed mainly on a hand-fed C&P. Some times the artwork (photo engravings, woodcuts and wood engravings) are printed on a Vandercook #4 or on a Washington hand press. We publish mostly Kentucky writers in two editions. The regular edition is printed on fine machine made paper, and since 2005 hand bound at the press. The special editions are printed on Moldmade or handmade paper and hand bound, usually with decorated papers over boards."

Enjoy these few examples, and give them a visit if you're in the northparts of Kentucky.

Wendell Berry Visits the Swannanoah Valley

The house was packed last night at Warren Wilson College for an evening reading and discussion with author and farmer Wendell Berry. Wendell, accompanied by his sweet wife Tanya and daughter Mary Berry Smith, was his usual charming self, slow to speak, intentional in word, full of joy. He read a short story written from the perspective of Martin (Mart) Rowenberry, a response, or conclusion even, to the story "Making it Home" which appears in Fidelity. It was a wonderful reading, about an hour in length, walking us through the mind and thoughts of Mart Rowenberry, 40 years after his return to Kentucky from WWII. There was a great dog/squirrel chase scene about mid-way through, appropriate for this time of year for those of us dog owners living amongst the oaks :) Don't know when he'll be publishing more Port William stories, but I'll be on the lookout. His upcoming New and Collected Poems will be out in April 2012.

And, for the smile of it, a shot of Wes Jackson of the Land Institure, Wendell, and Tanya. Photo by Dennis Dimick.

October 28, 2011

Meat...Camp

Not sure where this image came from, but obviously someone was inspired after passing through the salty little hamlet just outside of Boone, NC (Watauga County). If you ever need to know anything about Meat Camp, stop in and see Pat Beaver at ASU's Center for Appalachian Studies. Wikipedia has this to offer: 'Situated along the Old Buffalo Trail and established before the Revolutionary War, Meat Camp was the location where hunters stored there dressed animal carcasses until they were ready to return to their homes in the lowlands.' Pretty cool.

October 23, 2011

Great New Work By Charles D. Thompson

Spirits of Just Men tells the story of moonshine in 1930s America, as seen through the remarkable location of Franklin County, Virginia, a place that many still refer to as the "moonshine capital of the world." Charles D. Thompson Jr. chronicles the Great Moonshine Conspiracy Trial of 1935, which made national news and exposed the far-reaching and pervasive tendrils of Appalachia's local moonshine economy. Thompson, whose ancestors were involved in the area's moonshine trade and trial as well as local law enforcement, uses the event as a stepping-off point to explore Blue Ridge Mountain culture, economy, and political engagement in the 1930s. Drawing from extensive oral histories and local archival material, he illustrates how the moonshine trade was a rational and savvy choice for struggling farmers and community members during the Great Depression.

Local characters come alive through this richly colorful narrative, including the stories of Miss Ora Harrison, a key witness for the defense and an Episcopalian missionary to the region, and Elder Goode Hash, an itinerant Primitive Baptist preacher and juror in a related murder trial. Considering the complex interactions of religion, economics, local history, Appalachian culture, and immigration, Thompson's sensitive analysis examines the people and processes involved in turning a basic agricultural commodity into such a sought-after and essentially American spirit.

Another good story and video on the project can be found on the Southern Spaces website.

October 23rd, Already?

Sorry folks, it's been awhile. It's been a busy couple of months of life and work, closing up projects and starting new ones, packing boxes and relocating across town, playing with nieces and nephews and our new brown pup. We also packed the car and headed north with Radical Roots a couple times this month, once to Eastern University near Philly and once to Houghton College in western New York. Thanks to all of you who made those trips happen, to all of you who attended, to all of you who inspired me through late night conversations and early morning pots of coffee. As the leaves are falling and the night is coming sooner, I'm hoping to pay more attention to the blog. So...let's get started.

July 30, 2011

Counting Songbirds

Awkward name, yes, but Garden & Gun Magazine has some pretty decent writing from time to time. Like this months piece by Kentucky author Erik Reece (Lost Mountain & American Gospel) about a weekend adventure with Wendell Berry and a handful of Port Royal pals. I think you're going to like it...

It is eight in the morning on the last day of the world. We are standing, six of us, alongside the county road that cuts across Wendell Berry’s farm near the small Kentucky town of Port Royal. To our right, the Kentucky River has retreated back inside its banks after a tempestuous spring. In the lower pasture, a single llama guards Wendell’s sheep against coyotes. Up on the hill to our left stands the Berrys’ traditional white farmhouse as well as several busily occupied martin houses. The birds are what bring us here each May, but radio preacher Harold Camping’s doomsday prediction that the world will end tomorrow, May 21, has lent today a kind of cosmic, I mean comic, significance. “Well,” Wendell says, wearing khaki work pants and a team sweatshirt from one of his granddaughters’ high schools, “if this is our last day, we might as well have as much fun as we can.”

“No better place to do that,” says botanist Bill Martin, and we all nod our agreement. Besides Bill, our coterie consists of wildlife biologists John Cox and Joe Guthrie, me, Wendell, and his retired neighbor, Harold Tipton. Wendell, Bill, and Harold are of one generation; John, Joe, and I are of another. Some semblance of this group has been congregating here for the past eight years. The official nature of our business is to count and identify birds—migratory warblers and summer residents. But our pursuits might better be described in terms of what Wendell calls a “scientific quest for conversation.” As much as anything, we come to hear and to tell stories.

Wendell has been telling the story of this land for nearly five decades. A few hundred yards upstream from where we have gathered stands his writing studio, an approximately sixteen-by-twenty-foot room that overlooks the river and was the subject of an early essay, “The Long-Legged House.” Sitting atop tall stilts, the “camp,” as Wendell calls the studio, slightly resembles a great blue heron standing silently on the riverbank. It has no electricity, but natural light flows in through a large window, over a long desk where Wendell has written more than fifty books of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction, and in the process has become known as a leading writer on the subjects of conservation and land stewardship. “It is a room as timely as the body,” Wendell wrote in a recent poem,

As frail, to shelter love’s eternal work,In tumultuous and uncertain times, it is worth being reminded that these fine things—beauty, faith, gratitude—still lurk eternally beneath history’s dark veneer, and that an artist working alone in a room beside a river may catch a glimpse of them and render them into a lyric poem, a short story, or an essay.

Always unfinished, here at water’s edge,

The work of beauty, faith, and gratitude

Eternally alive in time.

Because of that work, President Obama awarded Wendell the National Humanities Medal in March at a White House ceremony. As he was presenting the award, the president told Wendell that reading his poetry had helped improve his own writing. It is an impressive remark, given that Obama is one of the best writers, along with Jefferson, Lincoln, and Grant, we’ve ever had as president.

Read more HERE.

story via: gardenandgun.com/article/wendell-berry

image by guy mendes

July 26, 2011

I Cannot Go Away

Heritage

James Still

I shall not leave these prisoning hills

Though they topple their barren heads to level earth

And the forests slide uprooted out of the sky.

Though the waters of Troublesome, of Trace Fork,

Of Sand Lick rise in a single body to glean the valleys,

To drown lush pennyroyal, to unravel rail fences;

Though the sun-ball breaks the ridges into dust

And burns its strength into the blistered rock

I cannot leave. I cannot go away.

Being of these hills, being one with the fox

Stealing into the shadows, one with the new-born foal,

The lumbering ox drawing green beech logs to mill,

One with the destined feet of man climbing and descending,

And one with death rising to bloom again, I cannot go.

Being of these hills I cannot pass beyond.

The United States of Poetry series offers this video of "Heritage" shot on the grounds surrounding Still's cabin.

James Still

I shall not leave these prisoning hills

Though they topple their barren heads to level earth

And the forests slide uprooted out of the sky.

Though the waters of Troublesome, of Trace Fork,

Of Sand Lick rise in a single body to glean the valleys,

To drown lush pennyroyal, to unravel rail fences;

Though the sun-ball breaks the ridges into dust

And burns its strength into the blistered rock

I cannot leave. I cannot go away.

Being of these hills, being one with the fox

Stealing into the shadows, one with the new-born foal,

The lumbering ox drawing green beech logs to mill,

One with the destined feet of man climbing and descending,

And one with death rising to bloom again, I cannot go.

Being of these hills I cannot pass beyond.

The United States of Poetry series offers this video of "Heritage" shot on the grounds surrounding Still's cabin.

July 25, 2011

Make No Mistake: Gillian Welch's The Harrow & The Harvest

Gillian Welch and David Rawlings are back at it, finally. On June 28th, Welch, with her 1956 Gibson J-50, and Rawlings, with his 1935 Epiphone Olympic, released The Harrow & The Harvest, their first new album since 2003. The stories woven into the minimalist guitar and banjo work are rich and varied (see interview with NPR's Terry Gross), but there's another interesting and unexpected story about the album. Check it out...

Interview With Judy Bonds in the Earth First! Journal

The latest addition of the Earth First! Journal includes a few pages of my late 2009 conversation with mountaintop removal activist Judy Bonds. Sadly Judy passed away on January 3rd at the age of 58. Since her passing, this conversation has taken on a new meaning to me, and her words are as relevant now as ever. Thanks to Russ McSpadden and the team at Earth First! for bringing this to print. Check the EF! website for future updates on the Journal and the continued work of the organization. It's with great honor that I share Judy's story with you. (Click photos to enlarge the text).

New Release From Appalachian-Andean Artist Jack Herranen

Check out the title track from the new album by our good friend Jack Herranen. You can order the album Runa Blues on his website: www.jackherranen.tennesseefolk.com

From Jack's website: Kumana is Aymara for a bundle of ceremonial elements and offerings. In Quechua to be a Runa is to be a dignified, rooted, communal being always in conversation with, inseparable from, the communities of spirits and the myriads beings of the natural world. In the great rush towards the false lights of some “better future progress” and “First World ideals” the term acquired a negative and venomous connotation in the mouths of the proponents of these goals. “These damn backward Runas! If they would just give up their old ways, become productive individuals, then we’d ALL progress!” Hell, we’re all familiar- and many of us have felt- this painful story. “These hillbillies/ol’ farmers/rednecks/ indians/blacks/wetbacks a- takin’ our jobs!!”

Our band Kumana is the creative tapestry woven by several extraordinary Bolivian and North American music partners. "Runa Blues" is our first record. It is the full manifestation of the Appalachian-Andean cultural conversation that has been underway for more than a decade. We recorded the bulk of this new music in Cochabamba with an exciting medley of talented folks from Cochabamba, El Alto, La Paz, Italy, and Detroit via Los Angeles.

"Runa Blues" is now deepening its Appalachian roots with the impeccable musicianship of some of the core members of The Bearded, one of southern Appalachia's favorite string/Old Time bands. Two of Knoxville’s hardest-working recording engineers (Nick Corrigan & Brian Wojtowicz) have been instrumental in harnessing the spirit of the work, in the exquisite music store/recording studio environment of Morelock Music right on historic Gay St. in downtown Knoxville. Sound engineer/musician/professor T.J. Jones is chief engineer for the mixing and mastering of this intercultural musical tapestry.

Inside Kumana's blues there is no feeling of defeat. It is the creative space where dignified rebellion is safeguarded. This music collection is an homage to campesinos, miners, working class folk, indigenous brothers and sisters, African-American and Latino comrades…the folks often pinned beneath the wheels of progress. Each song is a musical dialogue that runs from the Appalachians to the Andes, a chorus of voices and melodies that arise from the “Venas Abiertas” of Las Americas.

The elements we bring are our different musical styles, the cultural and political struggles of our peoples, our spirituality and our histories. The songs are journeys along diverse pathways that embrace and extend through the wounded lands of Las Americas. They are sometimes calm, sometimes openly rebellious. Always festive, always meant to give nurturance, sustenance, warmth to the heart in calloused times.

The music is our kumana. We lay it at your feet amigos! It is music for regeneration and remembrance, a space for stoking the flames of festive rebellion and safeguarding the dignity of all of us…Runas. And remembering that…TODOS SOMOS HIJOS DE CAMPESINOS!

From Jack's website: Kumana is Aymara for a bundle of ceremonial elements and offerings. In Quechua to be a Runa is to be a dignified, rooted, communal being always in conversation with, inseparable from, the communities of spirits and the myriads beings of the natural world. In the great rush towards the false lights of some “better future progress” and “First World ideals” the term acquired a negative and venomous connotation in the mouths of the proponents of these goals. “These damn backward Runas! If they would just give up their old ways, become productive individuals, then we’d ALL progress!” Hell, we’re all familiar- and many of us have felt- this painful story. “These hillbillies/ol’ farmers/rednecks/ indians/blacks/wetbacks a- takin’ our jobs!!”

Our band Kumana is the creative tapestry woven by several extraordinary Bolivian and North American music partners. "Runa Blues" is our first record. It is the full manifestation of the Appalachian-Andean cultural conversation that has been underway for more than a decade. We recorded the bulk of this new music in Cochabamba with an exciting medley of talented folks from Cochabamba, El Alto, La Paz, Italy, and Detroit via Los Angeles.

"Runa Blues" is now deepening its Appalachian roots with the impeccable musicianship of some of the core members of The Bearded, one of southern Appalachia's favorite string/Old Time bands. Two of Knoxville’s hardest-working recording engineers (Nick Corrigan & Brian Wojtowicz) have been instrumental in harnessing the spirit of the work, in the exquisite music store/recording studio environment of Morelock Music right on historic Gay St. in downtown Knoxville. Sound engineer/musician/professor T.J. Jones is chief engineer for the mixing and mastering of this intercultural musical tapestry.

Inside Kumana's blues there is no feeling of defeat. It is the creative space where dignified rebellion is safeguarded. This music collection is an homage to campesinos, miners, working class folk, indigenous brothers and sisters, African-American and Latino comrades…the folks often pinned beneath the wheels of progress. Each song is a musical dialogue that runs from the Appalachians to the Andes, a chorus of voices and melodies that arise from the “Venas Abiertas” of Las Americas.

The elements we bring are our different musical styles, the cultural and political struggles of our peoples, our spirituality and our histories. The songs are journeys along diverse pathways that embrace and extend through the wounded lands of Las Americas. They are sometimes calm, sometimes openly rebellious. Always festive, always meant to give nurturance, sustenance, warmth to the heart in calloused times.

The music is our kumana. We lay it at your feet amigos! It is music for regeneration and remembrance, a space for stoking the flames of festive rebellion and safeguarding the dignity of all of us…Runas. And remembering that…TODOS SOMOS HIJOS DE CAMPESINOS!

July 10, 2011

Radical Roots at Firestorm Cafe in Asheville, NC

Radical Roots is pumped to have the project hanging at Firestorm Cafe & Books in downtown Asheville (next to the Thirsty Monk on Commerce St). Firestorm invited us to display the project for the next 6 or 8 weeks, so if you're in or around the Asheville area this summer, be sure to stop in and check it out. A new addition to the exhibit is lamented copies of the interviews next to each photo. People have been asking about that since day one, and I finally got around to it. Thanks for all your feedback.

Firestorm Cafe & Books opened its doors in May of 2008. Established as a worker-owned and self-managed business, we aim to provide community space, critical literature and an alternative economic model based on cooperative, libertarian principles.

Here you'll find a wide range of events, workshops, film screenings, fund raisers and presentations. Additionally, we serve food and beverages all day long. Our edibles include delicious treats baked on site as well as hot and cold sandwiches and salads. For your caffeine fix, check out our extensive tea and espresso menu. We strive to maximize our use of local, organic and fair trade ingredients.

Our literature selection is a unique blend of off-beat, underground and independently published materials that you won't find anywhere else in WNC! We carry titles by AK Press, Autonomedia, Chelsea Green Publishing, Feral House, Loompanics, Microcosm, Paladin Press and many many others.

Behind the curtain, Firestorm Cafe & Books is run without bosses or supervisors, relying instead on a horizontal workplace. Each worker-owner is responsible for both weekly shift work and a share of managerial duties. Decision making is achieved using a formalized consensus process in which each participant has an equal voice. This cooperative environment creates a more empowering and enjoyable workplace while strengthening the business itself.

The ownership structure we require precludes us from applying for 501(c)3 nonprofit status; however, we are committed to a not-for-profit model and we will reinvest 100% of our earnings in the community once we are able to compensate labor at the equivalent of a livable wage.

June 30, 2011

June 10, 2011

Excerpt From My Interview With Helen Lewis

This is a short excerpt from my interview with Helen Lewis about her early days teaching Appalachian Studies in Wise, VA. As a sociologist, scholar, community organizer, educator, and activist, Lewis has worked extensively throughout the region as Director of the Appalachian Center at Berea College, Director of Appalshop's Appalachian History Film Project, and Director of the Highlander Research and Education Center. At the young age of eighty-seven, she is semi-retired but continues to teach, write, consult and lecture. Lewis lives in the mountains in Morganton, Georgia with her three cats and stays actively involved with her local community. Interview and photograph may not be used without permission.

I’ve been in education nearly all my life, but I’ve always thought of myself more as an organizer of students than a teacher. I taught sociology at Clinch Valley College in Wise, Virginia for a number of years in the 60s and 70s. As a teacher I saw the value of studying sociology from the traditional academic perspective, but I felt strongly that people’s minds were most captivated through experience. So in my classes I had my students going out and talking to people in the community, conducting research in the courthouse, and taking fieldtrips to the places we were talking about. I wasn’t interested in picking up broken pieces in these rural communities but with changing the system itself—I wanted my students working for real social change. That’s what social work is all about, it seems to me.

When I first moved to Clinch Valley, strip mining was beginning, the mines were being mechanized, and the community was falling a part economically. A lot of families were leaving for Chicago, Cincinnati, and Detroit, any place they could find work. An enormous amount of local history was being lost with of all these rapid changes, so I designed my classes in a way that we could study and record the knowledge and experiences within local communities. Some of my students interviewed family members who worked in the mines while others collected oral histories of old time musicians in the area.

One of my early students, Jack Wright, had just come back from Vietnam and was a rock and roll musician. He didn’t have any particular interest in mountain music at that time, so I helped him arrange interviews with Doc Boggs and some of the other traditional musicians in the community. Beth Bingman, another student in that class, did an amazing study on a little coal camp in Esserville, a town that had thousands of coke ovens that burned and smoked and polluted the whole area. That community study took us into peoples homes who lived by the ovens, as well as into the businesses along the highway. These homes were in poor condition and didn’t have plumbing or running water. And the men were paid in script and many of the families were in debt to the company store where the script had to be spent. We put together a big book of all the stories we collected from each of these communities and put it in the library at Clinch Valley. It was about the only place where these stories were being told.

In my early years of teaching Appalachian Studies I had the students choose the topic we would study for the semester. So they would choose topic, come up with research questions, and help organize events and guest speakers throughout the semester. They were also in charge of planning a community forum every Wednesday night, a time where community members and students could come and learn about what we were doing and listen to a guest speaker. One semester the students chose to study music, so I asked Rich Kirby, a friend working at Appalshop, to make me a bunch of tapes of traditional ballads and other kinds of mountain music. My students listened to those tapes over and over, and then divided into groups to plan a community forum based on the musical tradition they had chosen. They were responsible for finding and booking the musicians, organizing the program, and running the show from start to finish. We had a little bit money to pay musicians, but some of the brought their grandmothers in to sing or play so it didn’t cost us much.

One semester we studied coal mining. We talked with strip miners, coal miners wives, and the owners of coal companies. At one of our forums we arranged for a few doctors from West Virginia to come and talk about black lung disease. The students thought we should invite disabled miners, so the doctors talked with the Black Lung Organization and let the word out that we would be happy to host anyone who was interested. We thought a hand full of folks might show up, but we ended up having to move the class to the gymnasium after over 450 disabled miners showed up. After the program the students set up a table and put up a sign that read, “To join the Virginia Black Lung Movement sign up here.” Well, there was no such thing as the Virginia Black Lung Movement! They started it right there out of that class.

That same semester Frankie Taylor wanted to study the tax records of coal companies in the region. So he took this adding machine—we didn’t have computers in these days—down to the courthouse and told them he wanted to see the tax records of all the coal companies working in the area. That was public information, of course, but they told Frankie, “You’re gonna get in trouble, boy. You can’t do this.” But that’s what Frankie ended up studying, and it did cause a little stir.

We also invited Jock Yablonski, the United Mine Workers (UMW) reform candidate, to come and speak at one of our community forums. He got back to me and said he was afraid to come to Wise County because it was a pro-Boyle county. Tony Boyle was the current UMWA president and widely known for political corruption and for taking sides with mine owners rather than the miners themselves. The head of the union in Wise, a Boyle supporter, knew that I had invited Yablonski, so he was not happy with what I was doing with my students. We couldn’t get Yablonski to come to Wise, so we went over to Grundy to see him speak. When the election came up my students helped set up and run the poles. These were the kinds of things that made the coal companies very upset with us. They were angry that I my students working with grassroots community groups, for digging through tax records, and for supporting union reform. The chancellor at Clinch Valley told me, “The Union is against you, and the coal operators are against you too. I’m having a hard time with this.”

I started receiving threats because the work I was doing with my students. Someone threatened to burn my house down. My husband, of course, was very upset with all of this. I was too much of an activist for him, something that was part of the break up of our marriage. But this was the kind of teaching I was doing, and the program was really good. It wasn’t time for me to stop. Each week all of these remarkable things were happening and I could see my students making all of these important connections between resource extraction and poverty. Instead of being removed from the social and economic problems of the region, they were study and understanding these issues through the curriculum itself.

While I was teaching these classes in Appalachian Studies I also taught a class called Urban Sociology. I didn’t think it would do much good talking about urban sociology without visiting urban areas, so during the January term I took my students to New York City for a few weeks. I made arrangements to stay at the YMCA dormitory in Mid-town, and we started a program learning about New York City’s Puerto Rican community. We wanted to explore the social and political issues Puerto Rican immigrants were facing in New York City and look for ways to apply those experiences to our context in Appalachia. So we went out and talked with immigrants, visited agencies, and met with community leaders. We met with the Black Panthers and with the New York chapter of the Young Lords, a group fighting for democratic rights for Puerto Ricans communities. The Young Lords set up community projects similar to those of the Black Panthers but with a Latino flavor, such as free breakfast programs, dental clinics, and community day care centers. One day we visited a church where the Young Lords were running one of their breakfast programs and met with one of the leaders. He told us his personal story and how the group came about. As he was finishing he told us, “Anytime you try to make any changes you get killed. There’s John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr. We’ll probably be next.”

We left the church and went to Times Square and into a record store. When we walked in Taj Mahal was singing “Oh Death,” a song written by Doc Boggs, the old coal miner from Norton who had been to our classes and who Jack had interviewed. When we walked outside I looked up at the news ticker and it read: Jock Yablonski Killed with Wife and Daughter. I couldn’t believe it. It was the most incredible experience standing there with all of these things converging. One of my students said, “Remember what that man said in the church?” So we went back to the dormitory and stayed up all night talking about what had happened and trying to understand how all the pieces fit together. You can’t plan those kinds of learning experiences.

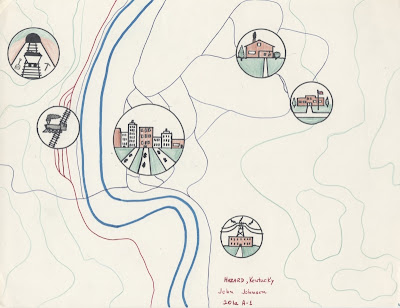

Mappalachia Project at Berea College

After World War II, Berea College created a general studies course called "Man and the Humanities," in which students studied literature, music, and art. One of the first assignments asked students to draw their home community. Over the four-decade life of this course, some 7,000 drawings were saved. Because many of the students who came to Berea during these years were from Appalachia, these drawings are now primary sources that offer revealing glimpses of Appalachian life over the last half of the twentieth century. Mappalachia is an effort to make the drawings accessible to scholars, alumni, and the wider public. For more information about the project or to view the gallery of maps, click HERE.

Was Abe Lincoln a Tar Heel?

Lincoln knew little about his family and apparently did not wish to pursue a genealogical investigation. He always said that his parents were originally from Virginia—that his mother was Nancy Hanks and his father, Thomas Lincoln, was the son of Abraham Lincoln, but that they were not connected to the wealthy New England Lincolns. Lincoln’s cousin Dennis Hanks, who, being of an age between Nancy and Abraham, grew up as friends of both, provided a few more details on the Hanks family. From Dennis Hanks Americans learned that Nancy Hanks was the daughter of Lucy, who was the sister of his mother, also named Nancy. The proclivity for Hankses to name daughters Nancy plays a significant role in the confusion.

Despite Lincoln’s own disregard for his genealogy, the general public, it seems, remained keenly interested in Lincoln’s family tree. The paucity of information, unfortunately, left room for fabrication. What likely began as an attempt to discredit the president during the Civil War has snowballed over the years. In 1861 a woman in Nelson County, Kentucky, told a newspaper reporter that Abraham Lincoln’s real name was Abraham Enlow and that he was a thief who ran off to Illinois and changed his name. She said that old Abe Enlow “has become a traitor president, under the stolen name Abe Lincoln. But we all said that [he] would never come to any good end.”

The connection between Abraham Lincoln and Abraham Enlow/Enloe/Inlow (the name and its variations were common in the early 1800s) would flourish. In March 1863 an article appeared in the Wilmington Journal stating that Lincoln was the son of Abraham Inlow of Hardin County, Kentucky. Later that year, a man wrote to Secretary of State William H. Seward to expose the president as “the illegitimate son by a man named Inlow.” The story of Lincoln’s illegitimacy found seed in many communities, especially those with Enloes and Hankses. About a dozen stories arose claiming to expose Lincoln’s true father, and of those, four were men named Abraham Enloe (or Enlow/Inlow). Besides Enloe, it was also said that Senator John C. Calhoun fathered Lincoln with Nancy Hanks, a South Carolina tavern keeper’s daughter. Some even said that Lincoln and Jefferson Davis shared a father. North Carolina boasted three fathers of the president—an Enloe, a Martin, and a Springs. However, the rumors that began as libel intended to discredit the Great Emancipator have become legends steeped in civic pride.

The North Carolina Abraham Enloe story first published in book form in 1899 by James H. Cathey as The Genesis of Lincoln is based on circumstantial evidence and oral tradition. In short, it is as follows: A young Nancy Hanks arrived in the state through various means, depending on the version, and ended up in the household of Abraham Enloe of Rutherford County. Abraham Enloe got Hanks pregnant and was forced to move west due to embarrassment. Most versions of the story have Hanks giving birth in Rutherford County after the Enloe family had moved on to Haywood County. Enloe then sent her to Kentucky and paid Thomas Lincoln, either a wandering horse trader or an itinerant farm laborer, to marry her. The birth took place, depending on the version, between 1804 and 1806, in order to fit the time frame of Enloe’s life. The legend also requires that Lincoln be born before his older sister, as Enloe would not have waited for the second child to send Nancy Hanks away. Lincoln’s ability to pass for three years younger, even as a small child, was explained by people’s accepting that he was simply “tall for his age.”

Documents related to Abraham Enloe can be found in the State Archives but ones that support his fathering Abraham Lincoln do not exist. A 2005 publication on the subject included several abstracted census records that are not true to the originals. For example, in presenting evidence from the 1800 federal census for Rutherford County, the author records a Nancy Hanks aged sixteen living in the household of Abraham Enloe. Not only does the 1800 census not provide names for anyone other than the head of household, but the author’s ages of the various household members do not match up with what is on the original. The author also merged at two or three Abraham Enloes in an attempt to prove the legend.

A 2003 book about Lincoln’s supposed North Carolina roots includes copious footnotes; however they lead the reader merely to secondary sources and oral traditions. The only original document mentioned in the book is the marriage license between Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks. Yet the authors discounted the veracity of the paper saying that even though it “was found in a courthouse,” there is no reason to believe that it is authentic. North Carolina’s Enloe is described by most proponents of the tale as a large slaveholder and slave trader and a man who made peace with the Cherokee. Records in the State Archives, however, show a man who owned at various times no more than four slaves (none in 1800) and a man who was involved in a lawsuit brought by Cherokee Chief Yonaguska.

The North Carolina story often described Nancy living with her drunken “Uncle Dickey” (Richard) Hanks. The “Uncle Dickey” story seems to be an attempt to make a Hanks connection whereby Nancy Hanks can be placed in North Carolina. The story goes that he could not take care of her, that he was an alcoholic who was often in jail, and as a consequence she was sent to live with the Enloes. However, records show Richard Hanks, who lived in Lincoln County and later Gaston, to be a man of responsibility and property. Court minutes do not indicate that he was a public nuisance. A Revolutionary War veteran, Hanks was supported in his claim for a pension by his clergyman. Finally, Nancy Hanks, the mother of Abraham Lincoln, did not have an uncle named Richard Hanks.

The entire effort to defend the legend is based on undocumented oral tradition and poor interpretation of the few available primary sources. Yet North Carolina’s Abraham Enloe legend endures and is, in fact, the focus of the Bostic Lincoln Center in Rutherford County. The mission of the center, www.bosticlincolncenter.com, is to research, document, and preserve the “generational lore” of Abraham Lincoln’s birth in North Carolina.

(via www.nccivilwar150.com)

June 6, 2011

Be With Me There

Those I Want in Heaven With Me (Should There Be Such a Place)

James Still

First I want my dog Jack,

Granted that Mama and Papa are there,

And my nine brothers and sisters,

And “Aunt” Fanny who diapered me, comforted me, shielded me,

Aunt Enore who was too good for this world,

And the grandpa who used to bite my ears,

And the other one who couldn’t remember my name—

There were so many of us;

And Uncle Edd—“Eddie Boozer” they called him—

Who had devils dancing in his eyes,

And Uncle Luther who laughed so loud in the churchyard

He had to apologize to the congregation,

And Uncle Joe who saved the first dollar he ever earned,

And the last one, and all those in between;

And Aunt Carrie who kept me informed:

“Too bad you’re not good looking like your daddy”;

And my first sweetheart, who died at sixteen,

Before she got around to saying “Yes”;

I want my dog Jack nipping at my heels,

Who was my boon companion,

Suddenly gone when I was six;

And I want Rusty, my ginger pony,

Who took me on my first journey—

Not far, yet far enough for the time.

I want the play fellows of my youth

Who gathered bumblebees in bottles,

Erected flutter mills by streams,

Flew kites nearly to heaven,

And who before me saw God.

Be with me there.

(photo via Appalshop)

March on Blair Mountain, Day 3

Last Saturday marked the start of the March on Blair Mountain, an effort to save the site of a historic labor battle from destruction by coal companies and to bring an end to mountaintop removal mining. (For updates on the March visit http://marchonblairmountain.org).

Expected to draw about 600 people, the march is organized by the Blair Mountain Coalition and Appalachia Rising, a movement that uses nonviolent direct action to advocate for a more sustainable future for the region. It commemorates the 90th anniversary of the 1921 Battle of Blair Mountain, when as many as 10,000 coal miners gathered in Logan County, W.Va. and faced off against coal companies and their private security forces in a bloody effort to unionize. The five-day battle was the largest armed insurrection in the United States since the Civil War and ended after the U.S. Army intervened.

Today there's a new battle on Blair Mountain -- this time over the fate of the land. Much of it is owned by Arch Coal of St. Louis and Virginia-based Alpha Natural Resources, which last week bought out Massey Energy.

Last year an alliance of environmental and historic preservation groups filed a lawsuit challenging the National Park Service's decision to remove the Blair Mountain Battlefield from the National Register of Historic Places, a move that leaves the land vulnerable to coal companies that have their sights set on mining the area. At least five locations within the battlefield have already been disturbed by mining, according to a report released last year by the Friends of Blair Mountain.

Just last week, six environmental and historic preservation groups petitioned the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection to declare the site unsuitable for surface mining "due to its historical significance, natural beauty and the important archaeological sites located there."

The march kicks off today in Marmet, W.Va., and over the next five days participants will walk 50 miles to Blair. The gathering will culminate in a rally and day of action on Saturday, June 11.

March organizers say that the current plans to mine Blair Mountain dishonor the memory of the scores of miners killed in the battle and will destroy one of Appalachia's most significant heritage sites. Among those who have called for preserving the site is United Mine Workers of America President Cecil Roberts, who earlier this year called Blair Mountain "as close to sacred ground as there is for the UMWA."

"As citizens in Wisconsin and across the country stand up to maintain their right to collectively bargain, Blair Mountain stands as a physical reminder of the struggles of previous generations of workers to establish those rights," says Brandon Nida, a Friends of Blair Mountain board member. "It is a place where a new solidarity for the 21st century will be forged between all of those fighting for workers, communities, and our mountains."

(via southernstudies.org)

Student-Based Oral History Projects

It's bright and sunny and warm here in the Carolinas. Still have to pull on a sweater at night, but it's nice to finally have the piles of quilts off the bed, the front door wide open, the garden in full swing. We could do without the carpenter bees. Any advice?

I've been working through the current issue of The Oral History Review, the journal of the Oral History Association. It has some excellent papers on the intersect of oral history and theology, the art of listening and reflexivity, oral history, democracy and civic engagement, and inter-generational memory collecting. The papers capture several obvious but essential elements of oral history; that history is not just about the great men and women of history books--kings and queens, presidents and statesmen, warriors and diplomats. Nor is it just about great events like wars and elections and natural disasters and stock market crashes. History is about and is shaped by the seemingly little people: the ordinary folk who in mundane and often imperceptible ways participated in and witnessed key events in our history. Their stories matter too.

Here are some examples of student-based oral history projects that are documenting the vital stories of such 'ordinary' folk:

Civic Voices: An International Democracy Memory Bank Project is building an inspirational and educational tool for transmitting the stories of the world's great democratic struggles from one generation of citizens to the next. It is a partnership between teachers’ unions and other partners in eight countries: Colombia, Georgia, Mongolia, Northern Ireland, the Philippines, Poland, South Africa and the U.S.

Fox Point Oral History Project: Through the Fox Point Oral History Project, graduate students in public humanities at Brown University work with community elders and with students, parents, and teachers at a neighborhood elementary school to document, preserve, and present local history.

Telling Their Stories--Oral History Archives Project: OHAP is a combination of a high school elective history course at The Urban School of San Francisco, a digital video oral history production protocol, a public Web site, and a growing collaboration with other educational institutions from around the country. Students learn oral history technique, conduct two-hour long video-recorded interviews, complete the transcription, edit movies, and publish to the OHAP website. Most OHAP interviews deal with witnesses of key twentieth century events involving acts of discrimination, including survivors, witnesses and liberators of the Nazi Holocaust, Japanese American internees, and elders involved in the southern Civil Rights Movement.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)